Psychotherapy for People Driven by Logic: How to Trust Your Emotions

Psychotherapy for People Driven by Logic: How to Trust Your Emotions

Key Points

-

People driven by logic are often high performers who achieve success through data and reason but may struggle with emotional interactions. They are seen as rational decision-makers and are frequently in leadership roles.

-

Logic-driven people seek clarity. They may trust using ‘head over heart,’ however, neuroscience shows emotions influence even logical decisions.

-

Many people driven by logic lack conscious access to their emotions, meaning they are not receiving the full range of available data.

-

Research shows that emotional disconnect, rooted in early life experience, can lead to relationship challenges and recurring behaviours.

-

Research also shows that disconnects can be repaired. Psychotherapy can help us connect and empathise with our emotions, which fosters the ability to connect more authentically with others. This leads to better relationships and improved overall well-being.

People driven by logic excel in using data and reason to navigate various aspects of life, often achieving remarkable success in business, career, or academia. Frequently they are leaders, and may pride themselves on using their ‘head, not their hearts.’ However, they might also struggle to understand what went wrong in close relationships, sometimes with seemingly ‘overly emotional’ people, or they might engage in patterns of behaviour that bring them little happiness.

Despite sometimes appearing non-emotional, avoidant, or even angry or dismissive, the decisions and behaviours of even the most logic-driven people are still influenced by emotion. Recent studies in affective neuroscience suggest that emotions play a role even in logical decisions. Emotions help us judge and place value on facts, integrating with our decision-making processes, whether we are aware of them or not.

However, people driven by logic do not always have conscious access to these feelings and emotions, making them unaware of the full reasoning behind their behaviour and decisions. Consequently, this can hinder their ability to connect deeply and consistently with others, leading to challenges in relationships and recurring behaviour patterns that feel insurmountable.

Psychotherapy is one modality that can offer logic-driven individuals a unique opportunity to explore and integrate their emotional landscape. By gaining a deeper understanding of their emotions, they can improve their relationships, experience personal growth, and enhance their overall well-being and effectiveness.

How then, might a person driven by logic approach such a journey?

Understanding The Hidden Struggles of High Performers

Step 1: Recognize Patterns

If you find yourself relying heavily on data and logic to navigate life, it’s possible that your deeper, unspoken needs and wishes have become dissociated, leading to a pattern of strained or broken relationships, or dissatisfying lifestyle patterns that seemingly repeat. Moreover, logic-driven individuals are often highly driven, high-functioning people, successful in careers, business, and academia. This might mask the fact they frequently struggle to access their full range of feelings and emotions.

Action: Take some time to reflect on your upbringing and personal history. We learn our first lessons from our parents, and it can take time to understand as adults how subtle or implicit some of those lessons were. Consider whether your emotions were shut down by your parents, or whether your parents modeled behavior that prioritised logic. Acknowledging these patterns is the first step toward understanding your emotional landscape. Bear in mind that this is a process and is much easier to do with a professional.

Psychotherapy for High Performers: Embarking on the Journey

Step 2: Prepare for Therapy

Entering the world of psychotherapy can feel like stepping into the unknown, especially for logic-driven high performers. It’s natural to feel unsettled or even scared. For someone accustomed to structured meetings with a clear focus, a one-on-one conversation centred on emotions and feelings might seem daunting or even impossible. However, logic can be an invaluable tool in this context. By using logical thinking, we can ask important questions and navigate the process more effectively. A skilled therapist can provide direction and ensure that logic is welcomed into the conversation. Continuously referring back to logical reasoning can help keep the process grounded and manageable.

Action: Approach therapy as you would any new journey. Start by orienting yourself: Where are you now emotionally? Where do you want to go? How will you get there? Think of therapy like mountain climbing—first, find a trustworthy guide. A good guide will help you stay anchored and encourage you to travel at a comfortable, safe pace. Remember, it’s important to pause and reflect on your progress regularly with your guide. This should be enjoyable—like taking in a wonderful view from a safe spot on the side of a mountain with a warm drink in hand! Lastly, ensure you feel comfortable giving honest feedback to your guide, and be honest with them if you don’t. Building a trusting relationship with them is key to your therapeutic journey.

Applying Science To Healing: A Modern Perspective

Step 3: Explore Research-Backed Modalities

Recent research in neuroscience and psychology has provided new insights into human experience and consciousness. It has been shown that adverse childhood experiences disconnect us from ourselves and can make empathy and relationship-forming difficult. Research has shown that techniques such as mindfulness, yoga, and psychedelics can effect positive change.

Action: Educate yourself on different therapeutic modalities. Consider trying practices like mindfulness, meditation, and yoga. In some countries, it’s possible to find legal psychedelic therapy or psychedelic exploration under professional guidance. Do diligent research about which modalities are suited to you. Check accreditations or references for individuals or organisations. Understanding different options can help you find the right fit for your healing journey.

Building Bridges: From Logic to Emotion

Step 4: Use Science-Based Resources

Modern psychotherapies leverage contemporary research to support the healing process. Facts, evidence, and body-based resources can help soothe and stabilise unsettled nervous systems, making it easier for strategic thinkers to connect with their emotions safely.

Action: Consider seeking a therapist trained in body-based psychotherapy practices such as Sensorimotor Psychotherapy or Deep Brain Reorienting. ‘Feelings’ can often be located in the body, therefore using the body as a source of information can give you a direct, experiential insight into what is happening beneath the surface. In short, it can help you safely build an effective bridge between your logical mind and your hidden emotional life. In summary, bringing your mind and body together can help you get a deeper, clearer understanding of your experience, helping you make sense of difficult relationships or patterns.

Embracing Your Unique Healing Journey

Step 5: Stay Open and Curious

Every human psyche is unique, and the healing journey is deeply personal. Although psychology can teach us about different patterns in people, and we may observe some of those patterns in ourselves, everything is in flux and neither our brains nor our bodies are in a fixed state. Therefore, with the right support, patience, self care, and willingness to put the work in, most people can evolve and effect change.

Action: Approach your therapy with curiosity and openness. Most importantly, remember that the steps or the process is not linear. We may need to repeat, try again, or try something different! Recognise that the discoveries you make about yourself—whether pleasant or challenging—can be valuable. Use these insights to nourish your ongoing journey toward self-transformation.

Igniting Transformation: The Power of Connection

Step 6: Reconnect with Yourself and Others

We were born to connect. Our ability to connect is a vital part of our humanity. Science tells us that life experiences can sometimes diminish this natural ability, even affecting the structure of our brains. Nevertheless, science also reveals that our brains possess the quality of neuroplasticity, meaning we can create new connections, both neurally and interpersonally.

Action: Focus on establishing meaningful connections with yourself and others. Therapy can help reignite this innate ability within you, enabling you to develop a more positive relationship with yourself. As you do so, you may find it easier to connect with others on a deeper, more authentic level. Remember the mountain climbing metaphor: it’s important to take a paced approach, stay anchored, use a good guide, and enjoy the new views and a wider perspective.

With growing societal support for mental health, now is the perfect time to embark on your path toward healing, transformation, and growth.

Get in touch!

Are you interested in learning more? Contact me for further information and availability. I work exclusively online and offer a free 15-minute Zoom consultation. This is a chance for us to get to know each other and see if we’re a good fit.

Share this article!

Know someone who might benefit from this article? Share it by clicking the links below.

San Quentin Prison: Trauma, Healing & Redemption

San Quentin Prison: Trauma, Healing & Redemption

James Fox was wolf-whistled by the inmates the first time he carried yoga mats through San Quentin prison yard. They saw yoga as exercise for girls. Fourteen years later and things are very different. When James led us through the cold steel entrance of the prison into the sunny exercise yard, we were met with smiles, fist bumps and introductions. We could hear James’ name being called from all directions.

My first experience in the prison building was witnessing fellow guest Josefin taking hefty, tattooed prisoners through a wild, theatrical Bollywood dance routine. Josefin combines trauma-sensitive yoga with trauma-discharging dance. Her immense, compassionate energy filled the room. She made it feel safe to explore. The inmates left calm, focused and grateful.

At the time of such trauma, the central nervous system buffers overwhelming pain. It shuts down parts of the brain involved in connection, emotion and feeling. This leaves the body feeling disconnected, or dissociated from the painful event. The individual may experience their body as a stranger or an enemy. The body however still holds the trauma.

Consequently, unresolved feelings such as fear, lack of self-worth and chronic self-blame develop into anxiety, depression, addictions and other mental health concerns. The result can be violent, chaotic and unpredictable behaviour.

Trauma has affected everyone in some way. For instance a relationship break up can trigger our early childhood wounds. When this happens, our unconscious mind wants to escape from pain. It tries different tactics to protect our vulnerability. We might self-soothe with ice cream, or seek solace in work, sex, drugs or alcohol. Obviously, this defense response can cause harm to ourselves and others.

However for some, the extreme nature of their trauma results in equally extreme outcomes.

Impressively, such mindfulness-based work is evidence-based. In the last two decades neuroscientists have proven that the brain can be retrained through yoga and meditation. Recently the Swedish prison system completed the largest ever Randomised Controlled Trial of yoga in correctional settings. The results concluded that yoga practice can play an important part in the rehabilitation of prison inmates.

Most men will enter prison believing masculinity means withstanding pain. PYP teachers respond to this by using the body as a metaphor: if you push it too hard, it breaks. Of course, this holds relevance to anyone who has experienced self-punishing behaviour.

Most importantly, a mindfulness-based practice explores the edges between comfort/discomfort and effort/non-effort. It provides a useful exercise in empathy, self-compassion and self-control. By repeating such practices, inmates become more sensitive. They see how much pain they have routinely caused themselves and others. They see how trauma has impacted on their behaviour.

“I have been hurt, and so I hurt others.”

Naturally, it requires strength and bravery to admit vulnerability, especially in a prison environment. It usually takes multiple personal catastrophes before an individual is ready to address their trauma, and hence PYP teachers provide important support. This is equally true for those of us making changes on the outside of prison, where we might feel supported by mindfulness, yoga and/or psychotherapy.

James took us to a different part of the prison after each yoga class. We met the newspaper team at the San Quentin News. In 2012 they were handing out newsletters within the facility. They have now grown to distributing quality newspapers to 69 prisons across the USA. We were interviewed by the award-winning prison radio station. We found both prisoner-run departments focus heavily on issues such as victim support and offender education programmes.

During these meetings I discovered I’d practiced yoga next to men who are giants in every sense. Men who are warm, compassionate, kind and charismatic. These men had received the support to achieve deep personal self-insight. In turn, they use their healing and growth to help others. Their self-compassion has led to compassion for others.

The men I met are leaders; they have achieved success against the odds and are driven to inspire others by example. It felt sad and unjust to think some might never get out.

It was raining as we tried to leave. We were unexpectedly held between locked gates at the prison exit. It was dark and there was only a tiny glimmer of natural light visible at the top of the gate. Everything went quiet. I could smell the damp stone and old metal. We waited and waited. I felt the pit of my stomach experience powerlessness, frustration, and uncertainty. I got a very small taste of what it’s like to live there. It felt like San Quentin prison was giving us a parting gift. A final lesson.

The gates opened and I felt a surge of relief to be outside again.

Thank you to Josefin Wikstrøm, James Fox, and the men and staff of San Quentin prison for making this experience possible.

This post is dedicated to the memory of Arnulfo Garcia, former editor-in-chief of the San Quentin News, and one of the fine men who inspired this article. Tragically Arnulfo was killed in a car accident two months after being released, at the age of 65.

Man up? How society affects men’s mental health. Psychotherapy in London

Man up? How society affects men’s mental health. Psychotherapy in London

How does society influence men’s mental health?

Men’s mental health has been much featured in the press recently. Stormzy and Prince Harry have discussed their own depression or trauma, encouraging other men to confront their own inner demons.

This has been fantastic in bringing greater awareness to men’s mental health. Phrases like ‘man up’, however, still exist.

‘Man up’, ‘grow some balls’ and similar expressions reinforce the ideas that masculinity means being able to withstand discomfort or pain, and that courage, bravery and resilience are male-only qualities.

These attitudes are damaging to men, their loved ones, and society.

First of all though, lets look at pain…

How does emotional/psychological pain or trauma manifest?

Historical pain and trauma is usually buried deeply in the mind/body, hidden away out of conscious awareness.

Pain and trauma projects itself both inwards and outwards. It can projects inwards as a dissociative ‘numbing out’ with alcohol or addictive behaviours (sex addiction, drug addiction etc), or depression, anxiety or eating disorders.

It can project outwards in the form of aggression, and/or controlling or manipulative behaviours.

Pain and trauma manifests in a multitude of ways, but generally as patterns of behaviour that render life unhappy, difficult, unfulfilling and painful.

So why not just ‘man up’?

Bracing against pain generally creates tension and brittleness. This is as true of the emotional or psychological as it is the physical.

The message we keep getting from Stormzy, Prince Harry, and countless combat veterans, prisoners and ex-prisoners is clear:

Bottled up emotions create a pressurised, destructive force that turn inwards, outwards or both.

Therefore, if we develop the ability to recognise when our internal forces are being destructive, we can effectively prevent such damage.

Martial Artist Bruce Lee’s advice was ‘be water, my friend’. He taught the wisdom of remaining flexible in response to one’s surroundings. Crucially, this means being able to be soft as well as hard. Lee understood that practicing such skills enhances mastery of mind, and body.

Bruce Lee, Be Water My Friend from Kim, sung-dong on Vimeo.

Does talking about how I feel make me less of a man?

‘Masculine’ qualities of strength, decisiveness, courage etc are useful and important to all humans. However, the unwise application of such qualities can undermine strength, rather than maintain it. Sun Tzu, the 5th century Chinese General, and author of The Art of War said that one of the five essentials for victory is “knowing when to fight and when not to fight”.

Masculine and feminine qualities exist within all of us. These qualities have nothing to do with our bodies, or gender. We can see such qualities when we explore the self in a safe and trusting space. This does not mean suddenly trading our lumberjack shirts in for a pair of high heels. Although for some of course, it might.

In this famous Monty Python lumberjack song, the singer’s fellow men are so appalled by his confessions that they run away. The lumberjack is baffled as to why his sharing the joys of cross dressing AND being a lumberjack have been so badly received. His female companion cries out “I thought you were so butch‘, bitterly disappointed at his hapless confession.

Clearly, he is left wondering…Is it not acceptable to enjoy both?

The lumberjack song is over 40 years old, and it is still seems funny to see a traditionally ‘male’ man unselfconsciously explore a different, more ‘feminine’ side of himself. We now have artists like Grayson Perry and Eddie Izzard proving that it is possible to be at ease moving between different aspects of their own male and female identities. They remain in the minority. Most men still fear ridicule and rejection if they choose to step outside of imagined boundaries of acceptability. These boundaries are created by society and enforced by self. They form prison walls that crush creativity, authenticity and true spirit.

And to be clear. The issue here is not just about transvestism. It is about feeling able to honour whatever is within; with self-compassion, and self-acceptance.

How can psychotherapy help?

Seeking support is a proactive and responsive way of acknowledging pain and discomfort. Not everyone wants to be like the lumberjack in the Monty Python video. Not everyone feels safe to stand in front of work colleagues or a partner to explore their deepest needs, fears, or hopes. Sometimes it’s safer to explore with someone who you don’t know socially. Someone you feel confident won’t judge.

A broken ankle might mean a visit to A&E to get a cast. A cast helps to hold, and contain such brittleness whilst new pathways are developed. With such support, flexibility, and a deeper, more integrated strength can be developed.

Psychotherapy works in much the same way. It is an opportunity to heal and to grow. It’s an opportunity for men’s mental health to be just as important as their physical health.

How can I find out more?

I offer a free 15 minute telephone or Skype/Zoom/Facetimeconsultation if you would like to discuss whether my work might be relevant to you. I’m based in Harley St, in London W1, but work internationally via Skype/Zoom/Facetime. Please get in touch now!

Image of Jon Gee courtesy of Bernardo Conti

This article is dedicated to the memory of Sophie Emma Rose. A true adventurer and journeywoman.

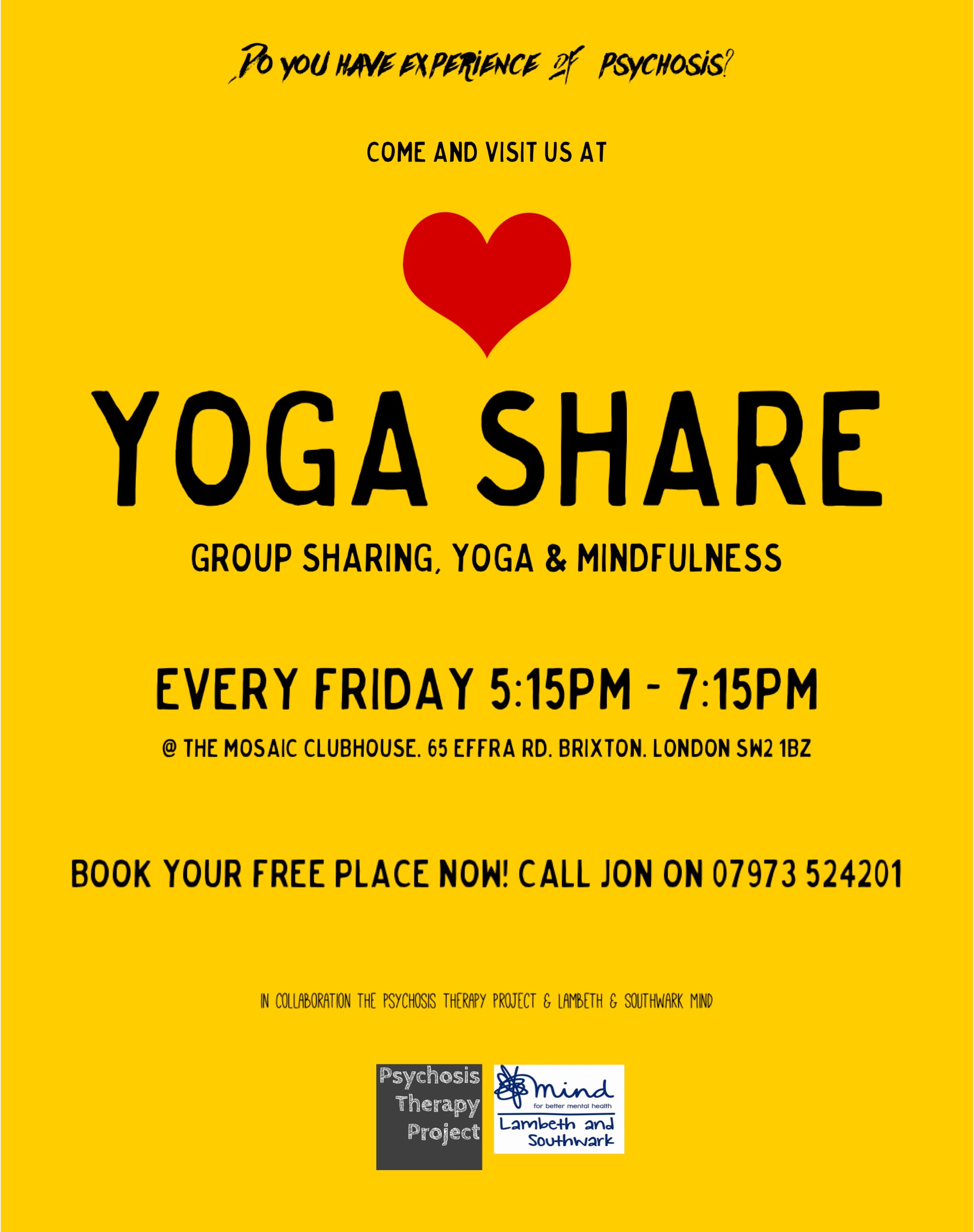

Yoga, Mindfulness and Group Psychotherapy for Psychosis in Brixton

Yoga, Mindfulness and Group Psychotherapy for Psychosis in Brixton

Why yoga, mindfulness and group psychotherapy in Brixton?

When I worked as an Honorary in a Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) for South London and Maudsley (SLAM) NHS Trust, I met many folks whose psychosis had been brought on by an accumulation of stressful life events.

My own experience (as well as countless studies) of yoga, mindfulness and group psychotherapy demonstrates that they provide very real tools for coping with stressful situations. With practice, we can develop a ‘radar’ that allows us to see potential problems on the horizon.

It got me thinking – why not offer such a combination for those who experience psychosis?

How is stress a factor in psychosis?

Stress is a major factor in all mental health conditions, whether psychosis, PTSD, bipolar and/or personality disorders. When we feel stressed, we are in the ‘fight, flight or freeze’ mode. In this survival mode our vision becomes narrowed, we see the world as threatening. Our coping strategies will be more likely to surface.

Such coping strategies might be addictive behaviours such as drinking, taking drugs, or engaging in risky sexual activities. It might involve acting defensively or aggressively in work or social situations, or it might involve pushing ourselves harder at work. It might involve all of the above – and more besides!

The combined forces of psychological, emotional and physical stress makes a psychotic episode more likely.

What is psychosis?

The experience of psychosis is unique to each individual affected by it. It might include delusions such as hearing voices, hallucinations, or unhelpful or confusing thought patterns.

It can feel very frightening to have such experiences. Such delusions might not appear real to anyone else, but they feel very real to the person experiencing them.

How can yoga, mindfulness and group psychotherapy in Brixton help?

Yoga Share aims to provide a small, contained group where attendees can share their experiences in a safe, non-judgemental space. Some folks might like to attend and say nothing – that’s fine! Some might have had a difficult day, and wish to curl up under a blanket with a cushion – that’s fine too – and there’s blankets, mats and cushions provided!

For thousands of years, yoga, mindfulness, and talking to each other has been a supportive way of dealing with the challenges that life throws at us.

Yoga Share aims to share some of that knowledge, in a healing space.

When/where?

Fridays 5:15pm -7:15pm at the Mosaic Clubhouse, 65 Effra Rd, Brixton, London SW2 1BZ. It begins on March 17th 2017.

This project is in collaboration with the Psychosis Therapy Project, Lambeth and Southwark Mind, and the Mosaic Clubhouse.

UPDATE 22/06/19: AFTER MORE THAN TWO WONDERFUL YEARS THE LAST YOGA SHARE TOOK PLACE ON 21/06/19. Thank you to all those who came, shared, supported and gave feedback. It was an amazing experience and I will never forget the kind and inspirational souls I met. There is still a general yoga group that meets at Mosaic on Fridays – please get in touch with Mosaic to find out more.

Why does it feel so difficult to talk?

Why does it feel so difficult to talk?

What are the commonest ways of dealing with pain or difficult feelings?

We might deny or repress our pain. We might hold it tight in our bodies, hunching our shoulders, or clutching our stomachs.

Or we might withdraw completely, and become silent and dissociated from our pain.

This list is not exhaustive, and sometimes a combination of these ‘coping strategies’ takes place.

Depression, self-harm, anger issues, addiction or otherwise destructive behaviours can all be indications of pain, a result of unresolved emotions or trauma. However, even if we ‘know’ the reasons behind our behaviour, it can be incredibly hard to learn new ways of being.

Why is it so hard to talk about feelings?

Our ego, or sense of identity can become constructed on the belief that we must stay ‘strong’ and ‘in control’. The thought of expressing ‘weakness’ can be experienced as destabilising and quite frightening. This in turn leads to increasing ‘armouring’ of the frightened ego.

We are trying to stay safe.

Perhaps our upbringing taught us that emotions should not be discussed.

Or perhaps emotions were so chaotically expressed by our family members, that we retreated into ourselves, to a place of safety.

Why is it useful to talk about feelings?

In doing so, there is less weight bearing down upon the structure of the whole house. Things can feel lighter, easier and more spacious. This space allows for new things to develop, relationships, attitudes and ways-of-being.